Amy and I were always taught that God doesn’t judge sins differently from one another, that all sin is the same, and this became the lens through which we read scripture.

But what does scripture actually say, and how did the early church interpret venial sins, mortal sins and the power of confession?

In scripture, we see a clear differentiation between different types of sin –

“If anyone sees his brother sinning, if the sin is not deadly, he should pray to God and he will give him life. This is only for those whose sin is not deadly. There is such a thing as deadly sin, about which I do not say that you should pray. All wrongdoing is sin, but there is sin that is not deadly.” 1 John 5:16-17

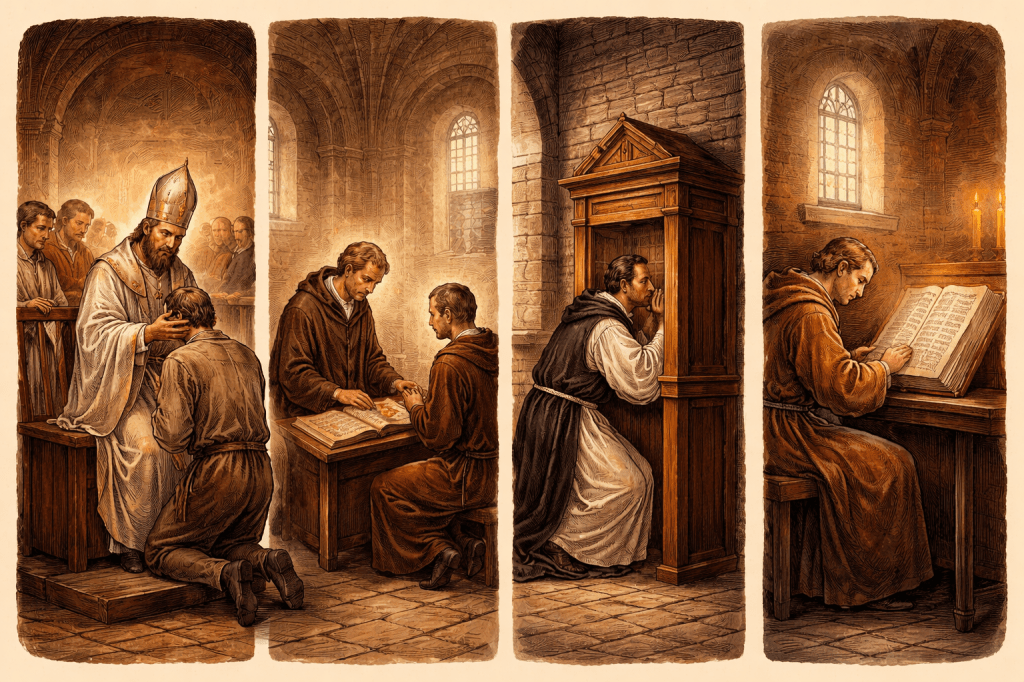

This is why God gave us both the gift and the power of confession. And why that power to forgive was given to his apostles, and ultimately their successors. We see this both in scripture, and the early church.

From scripture – “[Jesus] said to them again, “Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, so I send you.” And when he had said this, he breathed on them and said to them, “Receive the holy Spirit. Whose sins you forgive are forgiven them, and whose sins you retain are retained.” John 20:21-23

From the early Church – The early Church held a clear and unified understanding of sin, repentance, authority, and continuity that predates later theological labels but fully supports their underlying concepts. From the beginning, Christians believed that not all sins were equal. Scripture itself distinguished between sins that lead to spiritual death and those that do not (cf. 1 John 5:16–17), and the earliest Christian writings reflect this distinction. Grave sins such as idolatry, murder, adultery, and apostasy were understood to sever a believer’s communion with God and the Church unless repented of, while lesser sins wounded the soul but did not destroy grace. Although the terms mortal and venial developed later, the reality they describe was firmly embedded in early Christian belief and practice.

Because serious sin endangered salvation, the early Church treated repentance and confession as concrete, ecclesial acts rather than purely private experiences. Confession was ordinarily made within the life of the Church, often publicly in the earliest centuries, and was accompanied by real penance and reconciliation. Early Christian sources such as the Didache instruct believers to confess their sins in the assembly, and Church leaders consistently taught that restoration after grave sin required submission to the Church’s discipline. This practice flowed directly from Christ’s commission to the apostles to forgive or retain sins (John 20:21–23). While private, one-on-one confession developed later for pastoral reasons, the core conviction remained constant: Christ forgives sins through the ministry of those He authorized.

As Christian populations grew, public confession became pastorally difficult and spiritually discouraging for many believers. During this period, confession increasingly took place privately before the bishop or a priest, while reconciliation remained public. This transitional approach is seen in late patristic writers and regional practices, particularly in the East and West, as the Church sought a more merciful and repeatable way to restore sinners without abandoning apostolic authority.

The early Church also rejected the idea that salvation, once received, could never be lost. Baptism was understood to truly save and regenerate, but salvation was seen as a living reality that required perseverance. Persistent or unrepented mortal sin could forfeit the grace received in baptism, while repentance could restore it. Early Christian teachers repeatedly warned believers that returning to grave sin after coming to Christ placed one outside the Kingdom unless reconciliation occurred. Salvation, therefore, was not viewed as a one-time legal declaration, but as a covenant relationship sustained by grace, faith, obedience, and repentance.

Underlying all of this was the Church’s unwavering commitment to apostolic succession. The early Christians believed that Christ entrusted His authority to the apostles, who in turn passed it on to their successors—bishops appointed through the laying on of hands. This succession was essential for preserving true doctrine, maintaining unity, and ensuring the valid administration of the sacraments, including the forgiveness of sins. Writers such as Clement of Rome, Ignatius of Antioch, and Irenaeus appealed to apostolic succession as the definitive test of authentic Christian teaching. In their view, separation from the bishop and the apostolic Church was separation from the Church Christ Himself established.

Taken together, these beliefs formed a coherent early Christian worldview. Grace was real and transformative, sin had genuine spiritual consequences, confession and reconciliation were necessary for healing grave sin, salvation required perseverance, and apostolic succession safeguarded the Church’s authority and fidelity to Christ. Far from being later medieval developments, these convictions represent the ordinary faith and practice of the earliest Christians, rooted in Scripture and lived out in the life of the apostolic Church.

Leave a comment